It’s certainly not news that there’s been a lot of conversation in the health community for some time about the importance of probiotics, prebiotics, and microbiome health. In fact, we have been teaching about these topics for more than a decade in our Science of Raw Food Nutrition series of classes and our Mastering Raw Food Nutrition online and interactive program. We also created a webinar (see below for the video replay of it) to share with you our latest findings on this topic.

So, what exactly are probiotics? Simply stated, they are microorganisms with studied health benefits that can live in our digestive tract and compose our intestinal microbiome.

The most well-known probiotics include the bacteria lactobacillus acidophilus, bifidobacterium bifidum, and many more that have been studied and have become popular recently. Probiotics start to populate our digestive tract upon birth and establish a mutually beneficial relationship with us.

It’s important to understand the health benefits of probiotics, but there is one piece of the microbiome puzzle that is often omitted from these health conversations, which has to do with how to keep these important organisms viable in our GI tract.

How do these probiotics stay alive?

One important consideration is food. But what type of food is consumed by probiotics?

Do probiotics prefer the same types of foods that humans do?

The answer to this question, is partially yes. Because the preferred food of probiotics is certain types of fiber, which we as humans don’t digest or use as a food source. But many of the plant foods we consume contain these certain types of fiber preferred by probiotics.

Fiber that can provide nourishment for probiotics is referred to as prebiotic fiber or prebiotics.

Probiotics prefer certain types of fiber, but not all types. The one of the most plentiful types of fiber we find in whole plant food is called cellulose. Cellulose is composed of glucose molecules hooked together by bonds that cannot be broken down by our digestive system. In other words, the glucose in this fiber is not digestible or usable by us as humans because it is bound in the fiber complex, so it passes through our digestive tract largely undigested.

Here’s what cellulose looks like:

As you can see, cellulose is composed of a series of glucose molecules hooked together by bonds that are not digestible by humans.

By contrast, the fiber preferred by probiotic bacteria is composed of fructose molecules instead of glucose. We can’t digest this type of fiber either, but probiotic bacteria can digest it and it is their preferred food.

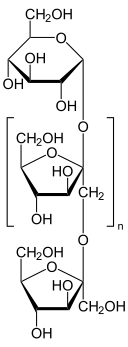

Here is an example of a fructose-based type of fiber:

Instead of glucose molecules hooked together by bonds, prebiotic fiber is composed of fructose molecules hooked together by bonds.

This type of fructose-based fiber would include both fructooligosaccharide (FOS) and inulin. There are others too, but we’ll focus on FOS and inulin in this article. These are two of the main types of prebiotic fiber found in plant foods.

Now, what exactly are FOS and inulin? They are each composed of fructose molecules and the difference between them is in the number of fructose molecules they each contain. FOS are composed of 2 to 10 fructose molecules. Some sources say 2 to 9. If we look at the term ‘fructooligosaccharide’ we see the fructo- which means ‘fructose’, oligo- which means ‘few’, and saccharide- which means ‘sugar’. So essentially, FOS are a type of fiber or undigestible sugar composed of few fructose molecules hooked together by bonds.

By contrast, inulin is composed of over 9 or 10 fructose molecules linked together by bonds.

Probiotics break down FOS and inulin into fructose and free fatty acids. The probiotics can then use the fructose as a food source. Because these prebiotics are probiotics’ favorite food, this creates a microbiome profile in favor of the probiotics. Additionally, the abundance of probiotics helps to keep the less desirable organisms in check.

What happens to the free fatty acids the probiotics produce?

They form into short chain fatty acids (SCFAs).

There are 3 short chain fatty acids, butyrate, propionate, and acetate, each of which has beneficial properties.

Butyrate, also referred to as butyric acid, is used by the cells of our large intestine (colon cells). Propionate or propionic acid can be used by the cells in our liver. Acetate or acetic acid can go to fuel peripheral tissues, such as our muscles.

Now that we’ve laid the foundation, here is the big question: where do we get the prebiotics FOS and inulin?

The good news is that FOS and inulin are found in more than 36,000 plant species.

Some examples of rich sources of FOS and inulin include: artichokes, leeks, shallots, jicama, dandelion greens, bananas, and many more. Even popular raw plant foods such as carrots, lettuce, raspberries, watermelon, and oranges as well as many others also contain prebiotics in smaller amounts as we’ll see shortly.

Is there an official recommended amount of prebiotics to consume daily? Because this is such a newly emerging field of study, there are no set US DRIs (Dietary Reference Intakes) for prebiotics. Researchers have been studying varying amounts for general health and therapeutic benefits. The research on prebiotics is an exciting work in progress and I’m looking forward to more in the coming years contributing to and clarifying what is currently known.

Even though we do not have a daily value for prebiotic fiber, we do have established DRIs (specifically Adequate Intakes – AIs) for total fiber:

- 25 g for women (21 g over 50 years of age)

- 38 g for men (30 g over 50 years of age)

To put these numbers in perspective, most Americans get around 15 g of total fiber per day. Standard western diets tend to be lower in fruits, vegetables, and whole plant foods in general so this number is not surprising. People on ketogenic and other types of low carbohydrate diets, which usually end up being low fiber diets, are likely not consuming this level of prebiotics either. Self-evaluation of one’s dietary approach would help determine where one stands on prebiotic intake.

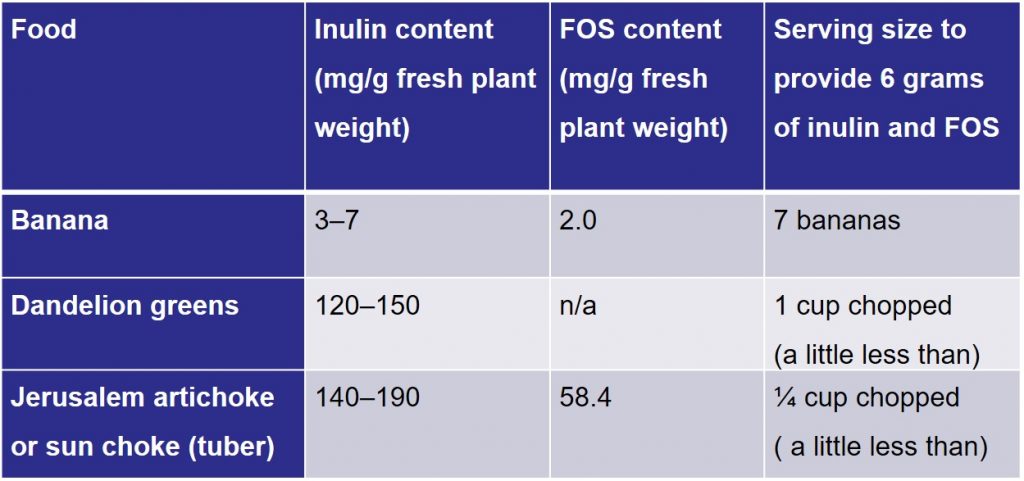

Getting back to our conversation about prebiotics specifically, here are some foods that are especially rich in prebiotics: bananas, dandelion greens, and Jerusalem artichokes (also known as sunchokes).

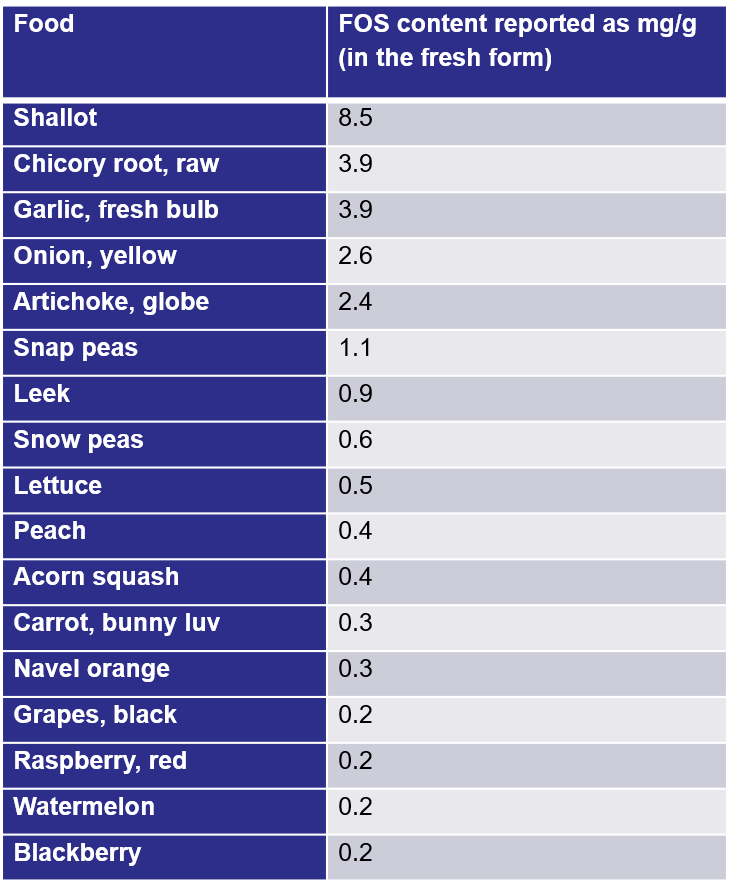

Here is the FOS content of certain foods. There are a number of foods that have been measured for prebiotic content, but many more that have yet to be measured. Hopefully more will be known in years to come.

It’s interesting to see the FOS and inulin content of individual foods, but what does the prebiotic content look like on a raw or plant-based meal plan. Here is an example of a couple of meals (not everything) that I ate on one particular day a couple of summers ago. On this particular day, I went for a long run, so that’s why I had a large fruit smoothie:

3 oranges

¼ cup blackberries

¼ cup raspberries

1 cup mango slices

3 cups kale

2 bananas

And here is the salad I had on that day. On many days it can be even larger than this:

2 cups dandelion greens

10 cups lettuce

1 cup carrots

1 cup cucumber

1 green onion

3 tomatoes

1 date

1 tablespoon chia seeds

1 tablespoon tahini

Juice of one lemon

The prebiotic content of these foods is at least 4.6 grams. The reason I say at least is because many of these foods have yet to be measured for prebiotic content, so given what has been measured, we can expect to find at least 4.6 grams of FOS and inulin in these foods and most likely more. However, the 2 cups of dandelion greens and 2 bananas were not included in the original calculation of the 4.6 grams, so when we add in the bananas and dandelion greens we actually see a total of at least 21.1 g of FOS and inulin! That’s amazing! This shows us that plant foods can provide a notable amount of prebiotic fiber and that certain plant foods like dandelion greens and bananas are extra-rich sources of these prebiotics.

As we can see, whole natural plant foods provide these and other beneficial types of fiber, which is just one of the many health benefits derived from eating whole natural plant foods.

What about the total fiber content of these foods?

Total fiber content is 61.1 g from these foods alone!! This is much higher than the average American intake of 15 grams of total fiber per day and the DRIs for total fiber.

For some added perspective, I usually eat more than this in a day so my total fiber intake is even higher than this.

And the information in this article is just the tip of the iceberg on probiotics, prebiotics, and raw food and plant-based nutrition!

The video of our webinar on this topic has additional information and explanations (see below). The information on prebiotics starts at around 16 minutes and 35 seconds and ends around the 30 minute mark. You can also learn more about us and our class Mastering Raw Food Nutrition by watching before and after these points.:

References and Research:

Brownawell AM, Caers W, Gibson GR, et al. Prebiotics and the health benefits of fiber: current regulatory status, future research, and goals. J Nutr. 2012;142(5):962-974.

Campbell J, Bauer L, Fahey G, Hogarth A, Wolf B, Hunter D. Selected Fructooligosaccharide (1-Kestose, Nystose, and 1F-β-Fructofuranosylnystose) Composition of Foods and Feeds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1997;45(8):3076–3082.

Davani-Davari D, Negahdaripour M, Karimzadeh I, et al. Prebiotics: Definition, Types, Sources, Mechanisms, and Clinical Applications. Foods. 2019;8(3):92.

Kelly G. Inulin-type prebiotics--a review: part 1. Altern Med Rev. 2008 Dec;13(4):315-29.

Lloyd-Price J, Abu-Ali G, Huttenhower C. The healthy human microbiome. Genome Med. 2016;8(1):51.

Markowiak-Kopeć P, Śliżewska K. The Effect of Probiotics on the Production of Short-Chain Fatty Acids by Human Intestinal Microbiome. Nutrients. 2020;12(4):1107.

Moshfegh AJ, Friday JE, Goldman JP, Ahuja JK. Presence of inulin and oligofructose in the diets of Americans. J Nutr. 1999;129(7 Suppl):1407S-11S.

Niness K. Inulin and oligofructose: what are they? J Nutr 1999; 129 (7 Suppl): 1402S – 1406S.

Slavin J. Fiber and prebiotics: mechanisms and health benefits. Nutrients. 2013;5(4):1417-1435.

Van Loo J, Coussement P, de Leenheer L, Hoebregs H, Smits G. On the presence of inulin and oligofructose as natural ingredients in the western diet. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 1995;35(6):525-52.

Vyas U, Ranganathan N. Probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics: gut and beyond. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012; 2012: 872716.